As DefExpo, India’s flagship trade show for land-based and naval armament, kicks off, it’s difficult to duck the fact that the flavour in the air is wholesomely aviation. India has billions of dollars worth of contracts in the navy and army space up for grabs, contracts that you’d think earn themselves more of a glare in the narrative buzz that surrounds DefExpo. But once again, it’s all about the third iteration of India’s ‘mother of all deals’.

As Livefist reported last week, India’s latest step out the door to buy over 100 fighter jets — and built most of them in India — hasn’t exactly electrified the raft of competitors whose product teams have quite literally spent more time in India in the last decade than they have in their own countries. The six firms that participated in the similarly configured and failed MMRCA contest, which aim most of their energies on India’s dedicated military aviation trade show AeroIndia, will be at DefExpo this year with a spring in their step. The spring, though, isn’t from their own levels of anticipation — nobody’s expecting things to move quickly — but in keeping with an MoD that has mobilised an extravagant campaign to make the government’s flagship ‘Make in India’ campaign look alive. It didn’t matter than DefExpo was constructed specifically as a non-aviation event. The MoD still went ahead and compelled the Indian Air Force to issue its request for information (RFI) for 110 fighters just days before the event, making it clear that this was the headline they wanted.

It’s a familiar, perplexing, frustrating loop of life. For over a decade, and reinforced in no small measure by the high-voltage MMRCA contest, India’s quest for fighter aircraft has been the talk of the global industry. Nobody can walk away from it, ignore it, quite understand it fully. And yet, here it is once again in a third iteration. If there was shock in the industry at the almost playful pulling of the plug recently from a declared requirement for single-engine fighter jets and announcing this mega ‘mother of all deals’ in its place, it was well disguised. But what the ten years have done is fashioned a narrow tunnel vision of perspective within the air force and government, where the need for platforms has trumped the desire for capability, where laying down the contours for missions India should be able to execute have been waylaid by an interrupted obsession with specifications and bean-count comparisons with Pakistan and China. All the moving parts of this complex machinery take solace from the one thing they stand unitedly yoked to without choice — India’s non-negotiable sanctioned fighter squadron strength of 42.

The prospective new contest to buy and build 110 foreign fighter jets in India has noble intentions embedded within its jumble of customised stipulations. The air force desperately needs fighters, as dictated by the ever trembling needle on the squadron barometer. But the equally emphasised thrust here is for the contest to give India, almost magically, an aerospace industry that steps beyond the restricted definitions of Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd (HAL), the only company in India that builds combat aircraft. To give India, in one fell swoop, the deep skilling and resource depth to be able to engender future flying machines of its own going forward.

And that’s where the AMCA comes in.

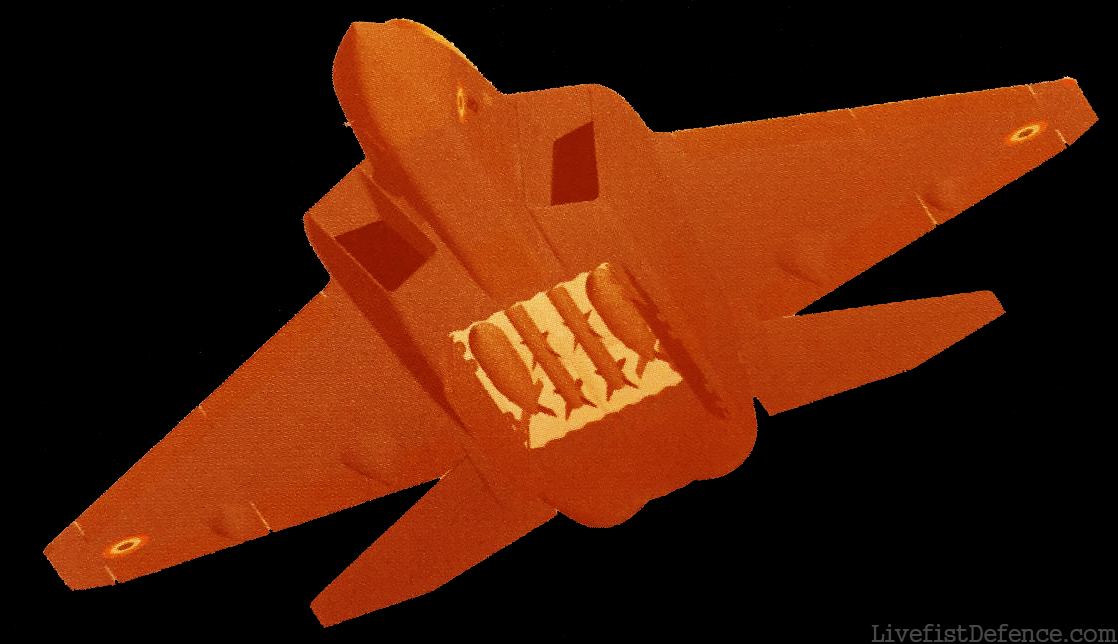

India’s Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft is a paradox. It is intended to be a test case for fundamental Indian research in the unfamiliar field of cutting edge aviation, and yet is poised to be anything but. It is to be the bankable future platform that India can take its time with, and yet never has there been a more perceived urgent need for aircraft with at least some of the capabilities that qualify as fifth generation. It was to be the seamless progression from the LCA Tejas, but its administrators are currently grappling with issues that are so deep set as to shake the project to its very core. It’s also one of the reasons why the Indian government has decided to yoke its quest for 110 new fighters with the fate of the AMCA.

The DRDO-administered Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA), which is concepting the AMCA has publicly said it is aiming to test-fly a prototype by 2020, with an aim to begin production of the jet by 2025. This target has now been reconfigured with an aim to fly the jet in seven years, that is by 2025.

To be sure, the Indian Air Force has been consistently incredulous of the DRDO’s overarching projections on the AMCA, playing ball in meetings that involve the Ministry of Defence at Delhi’s South Block, but openly displaying its lack of faith in smaller interactions away from India’s capital. The Indian Air Force would defend this as pragmatism based in no small measure on the experience of the LCA Tejas and the fact that it doesn’t have time — or money — to fool around with castles in the air. Therefore in 2015, even as the DRDO painted an elaborate and ambitious picture of the AMCA before a global audience, India’s air attaches in Russia, the United Kingdom, Europe and the United States informed industry that India’s next quest for fighters would need commitments towards the AMCA.

By 2016, vendors had integrated the AMCA into their India pitch. During the roll-out of the Gripen E, Saab emphasised what it could do for the AMCA, if India decided to go with the Swedish jet. Months later, Boeing unveiled an elaborate integrated plan that showed how building the F/A-18 would give India the sinew and know-how to develop and build the AMCA at the very same facility.

The DRDO may have vaunted ambitions with the AMCA, but has felt the heat. In a February meeting on the aircraft project in Bengaluru, DRDO chief Dr. S. Christopher had a singular message for the project team — that the AMCA couldn’t trundle down the path of the LCA Tejas. In an exclusive chat with Livefist that day, Dr. Christopher was sombre.

“What worries the air force is development and production schedules. Every time we talk of projects in India, we aren’t able to tell with confidence what the production schedule will be. Our current production rates are rarely over six aircraft per year, and aiming for 16. This is still less than the required number when you do the multiplication. And this is for the LCA. Now we have to think of the AMCA. This is what worries the air force,” he said, but asserted that the Indian Air Force was ‘fully supporting’ the project.

With the IAF managing to make the AMCA the collateral in India’s next foreign fighter-building effort, the DRDO has been freed up somewhat to focus on the debilitating issue of production.

“We are taking up a lead-in project and also trying to talk to various production agencies from the beginning, unlike in the case of the LCA where everything went through HAL,” he said. “HAL themselves are agreeing that they could be the lead and other companies could take care of other modules to speed up development and production. If we can make this timeline miraculously low, that would meet the IAF’s main requirement.”

Livefist can confirm that the DRDO has initiated and/or plans to initiate discussions with companies including Tata, Mahindra Defence, Larsen & Toubro and a slew of smaller specialised firms to discuss slicing up the AMCA and distributing responsibility.

The intensifying narrative around a so called ‘two-front’ war has piled the pressure on the DRDO in many ways to have something to show for efficiency and competence, following the troubled saga of the LCA Tejas. The LCA entered squadron service in 2016 and is turning several important corners towards final operational capability, but the aircraft program still has frustrating miles to go before it can truly realise its identity as a mass-produced jet for India’s large aviation needs.

While the DRDO has had its work cut out dealing with an unforgiving air force, its frustrations with HAL have also boiled over. But with no more manoeuvering space on budgets and timelines, the two agencies have found common cause in getting things right with the AMCA.

“I strongly feel it is because of the model we use. We’ve been in touch with HAL’s chairman and he also agrees we are both at fault. We simply make our design and talk to HAL and then both sides decide the other fends for themselves. We cannot afford to have this approach with the AMCA. It has to be perfect from the start and fully coordinated,” Dr. Christopher said.

Confirming the DRDO’s move to tap private Indian industry that already does major fabrication work for majors like Boeing, Airbus, BAE Systems and others, the DRDO chief told Livefist, “We are also looking for various vendors who can support us. Today the country has companies already working for Boeing in aircraft for instance, so why not we tap them to make some modules for the AMCA? That’s our next job.”

The DRDO chief informed Livefist that his team hoped to see an AMCA prototype take on its first flight by 2025.

Technologically, the AMCA is a project that runs concurrent to India’s Ghatak stealth unmanned combat aircraft. An integrated raft of laboratories in fact are currently researching common technologies for both platforms, including shape stealth, network-centricity, sensors and materials. But with a lions share of critical technologies now expected to be infused from the outside, it remains to be seen how much of the AMCA remains strictly Indian.

Livefist recently asked a group of international aviation journalists about the AMCA and its prospects to get an outside view on the path ahead.

David Cenciotti, who runs the popular Aviationist blog, told Livefist, “let’s keep it real: India can’t consider AMCA anything more than a dream now. The troubled development of the Tejas should be a reminder that the Indian aerospace industry is simply not ready for a domestic fifth generation aircraft without a significant foreign help. It might be ready in some decades, but most probably not in the foreseeable future. One might wonder whether the Indian Air Force needs a 5th gen. aircraft at all, considered that it still operates a large fleet of 3rd generation aircraft it still needs to replace.”

FlightGlobal’s venerable Stephen Trimble said, “AMCA is clearly India’s best option for preserving sovereignty and flexibility over the long-term, but it is the highest risk. The F-35 is the highest cost to operate and maintain, but provides the most capability for the lowest risk for at least the next 10 years. The FGFA lies somewhere between these two on the risk/capability/sovereignty curve. If I’m India, I’d probably hedge my bets. I’d double-down on low-risk capability in the near-term while continuing to fund development of the high-risk option with the greatest sovereignty in the long-term.”

Meanwhile, Hush-Kit’s Joe Coles was less generous. “The AMCA appears to be complete madness. Jumping from an unsuccessful (relatively) technologically pedestrian project like Tejas to a world class stealthy tactical fighter seems an unlikely route to success. Additionally, a first flight in 2025 (if achieved) plus ten or twenty years of development to get it operational sees it reaching squadrons in the 2035-45 period. At best, you have an F-35 twenty years too late (or mini F-22 thirty years too late). Of course an AMCA would have a large amount of foreign help (Russian and maybe Swedish), which may help matters, but looking at the FGFA, Russia does not seem a great collaborative partner.”

The IAF and DRDO have agreed to power the AMCA prototypes with GE F414 engines, through Dr. Christopher says the DRDO-Safran ‘Super-Kaveri’ engine is being kept as a future option. This has left the team to focus strictly on the airframe. But there’s a dilemma. With the AMCA moving ahead with an aim to fly a prototype by 2025, and little or no hope of foreign help trickling in any time soon (since the Make-in-India fighter program won’t be moving forward with anything approaching swiftness), will the aircraft that flies truly be the elaborate fifth generation concept its makers say it will be.

“We are moving ahead as fast as we can,” DRDO’s Christopher says. “When technology comes, we will make use of it. But for now, our best foot forward and fast.”

The variables and anxieties that cling to the AMCA, in many ways, are more than common for any complex and expensive aviation effort. The weight of practicality and the urge for sovereign technology may actually yield an impressive platform. But this being a country of competing interests and priorities, inter-service trouble over the AMCA has exploded even before the aircraft has left, literally, the drawing board.

Hitherto unknown, the Indian Navy has apparently been left out in the cold on the AMCA project, its requests and suggestions alarmingly ignored for over two years.

The navy first got ‘involved’ in the AMCA project in March 2013 when it formally asked the DRDO/ADA if they were planning a naval version of the program. The query sprung from the navy’s own internal activity at the time — it had started to analyse the sort of air wing it needs on the second in the series of indigenous aircraft carriers planned to be built (IAC-2).

A top Indian Navy officer speaking to Livefist but asking not to be named said, “In March 2013, a multi role Medium Combat aircraft was envisaged for the carrier. Given that IAC-2 was being planned for induction in 2030 timeframe, it was felt that early 2013 was a good time to encourage ADA to work on a Naval AMCA rather than having to repeat the mistake of LCA wherein attempts were made to navalise the Air Force variant of LCA. This never works. Didn’t work for LCA. Hasn’t worked well for MiG-29K or the Su-33 either. It hasn’t even worked well enough even for helicopters (ALH is a case in point).”

For reasons that may be many, the DRDO-ADA combine rebuffed the request, telling the navy it had no plans to develop a separate naval AMCA (NAMCA) unless the the navy committed itself financially and otherwise so it could ‘start work’. Naval Headquarters in Delhi then activated a team of aviators, from MiG-29K and Sea Harrier pilots to veteran flyers to finalise a set of ‘top level requirements’ for the proposed NAMCA. After a series of meetings with the ADA and DRDO, an official letter detailing these requirements was sent on 7 September 2015. Among other things, the Indian Navy requested for a separate team to be constituted for the development of NAMCA and sought involvement of naval representatives at all stages of the project.

“The DRDO/ADA has not yet been able to obtain approval from the government for the funding that may be necessary to carry out this feasibility study. Financial and personnel participation hasn’t even been sought yet by ADA. It hasn’t moved for over two years now,” the Indian Navy officer quoted above tells Livefist.

The situation is an alarming one. It demonstrates, in effect, that the AMCA is walking down at least one of the troubled paths trudged by the LCA Tejas. The navy wants a carrier-based version designed from the drawing board, not as a spin-off version of what is essentially a shore-based air force aircraft. Its experience with having to abandon the LCA haunts planners who, ironically, had expressed more open faith in the Light Combat Aircraft than their contemporaries in the Indian Air Force.

The navy, currently on the hunt for 57 carrier-borne fighter jets, is dismayed by what it feels is second-class treatment.

Ignored by the the DRDO-ADA on its 2015 request, the navy followed up with a more radical (well, for India) proposal — it asked at an MoD meeting whether it was not better and economical to simply start with the naval variant?

“We wanted to be cautious. We advised that ADA must have a naval variant to start with. It is, in fact, better to start with just one variant – the naval variant – since it is difficult to fund two development programs together,” says the navy officer. “The spin-off of mass reduction etc on the Air Force variant should be taken advantage of later. Case in point being the Rafale. They started with the Rafale-M. But, I don’t know who is listening!”

The navy, which is currently also grappling with an air force that is regarding the carrier-based fighter requirement with disdain, is seeing the AMCA emerge as a fresh turf war with its sister service. For a fighter program that intends to consolidate an overarching set of targets for India’s industrial aerospace complex, a pair of chagrined customers should already be clanging the alarm bells. But not yet.

The navy officer Livefist spoke to was deeply unhappy when he answered our question on this:

“I am surprised that some of them [in the IAF] do not understand that is one needs aviation capability at sea ‘here and now’. You cannot depend on shore based aircraft to provide support for either surveillance, or air defence or anti-submarine effort or even anti-shipping strike missions around the Task Force which is deployed some 700 odd nautical miles from the nearest Indian coast. The last two missions can be met partially by shore based planes when the Task Force is close to coast but the too inadequately. The first two can be met just negligibly, if at all – and that too at very close ranges from land – that’s not where a Task Force wants to be!

The navy’s top level requirements for the AMCA are graded secret. What Livefist has learnt is that the navy has diluted performance figures from the Air Force’s staff requirements to create space for development.

“This is since it is typically difficult to match land based aircraft’s performance requirements for a heavier carrier based plane (due heavier undercarriage etc),” the navy officer quoted above says. “But we have sought better over the nose visibility required for a tail-hook aircraft on approach for landing and capability to operate on both CATOBAR and STOBAR carriers (since we expect both our STOBAR carriers to be still around when the new CATOBAR, IAC-2 is envisaged to get commissioned).”

With overwhelming focus on the Make in India fighter program, the AMCA project sits on the lip of a crater. Far too many times in India’s past have intentions subdued execution and result. An indigenous fifth generation fighter deserves more concerted energies and administrative attention.

IF WE DON’T START NOW , WE WILL BE NEVER SELF SUFFICIENT . BETTER LATE THAN NEVER

India – learn to live with a sad truth – you cannot innovate, invent or be creative; nor anyone has the discipline required to realise such dreams, therefore you forever must accept your fate of being a servant to the rest of the world’s industry – build doors for Boeing aircraft or just service these……..it is not in your DNA to lead the world.

And it is this type of negative and insulting attitude of some misanthropes like you why we are SLOW. Maybe it’s time you get hold of some good science magazine, lest your radar should ever remain defective, detecting battleships as boats.

Like I said – learn to live with a sad truth. I have watched the Indian aero scene from the HF24 Marut onwards forever hoping for the day when India would be truly independent of the world’s military industry. But no, that is not going to happen. No one is going to give you the ability to manufacture your own modern jet engines. Kaveri is a relic. Jet engine technology started around 1931. So it has been around 88 years. India has been independent for 72 years. Even in 7 decades, it has not been able to overcome this hurdle. I have been reading about so called Technology Transfers for decades. But what good have these done. With India, if you show them how to tie a left shoe lace, they then want you to show how to tie the right shoe lace as well. How dumb can you get? But the ministers are very good at doing Shastra pooja on a piece of hardware that has not even yet become operational in Indian Airforce.

Exactly, The curent economic growth is not powered by indigenous innovative or inven.tion or products.

It is powered by temp foreign inc’s.

This is not real growth

R Kumar , ur wrong. its true that tejas programme was started in ’83 and yet ongoing. but its also a truth that it has obtained the speed since 2014. tejas is becoming better year after year. India is also working on the infrastructure needed for production. if we think about amca, tejas is a milestone. as per present speed, we can say time needed to complete amca will be lesser than tejas. moreover kaveri engine programme is too on speed.

Developing such aircraft requires a vast knowledgebase and skills built over a period of time involving diverse application areas. How many universities have involved in developing such knowledgebase? How much infrastructure we have for conducting advanced research? How much human resource we have who have inclination to commit their life for such research? How much funds do we have for such research?