In a major push to accelerate India’s next-generation stealth air combat capability, the government is preparing to shortlist two private companies to co-develop and co-produce the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA), the country’s long-awaited stealth fighter. At least five Indian defence majors have submitted bids to join the ambitious programme, with a stringent evaluation process now underway to identify the final partners.

Among those reported to have bid are Larsen & Toubro (L&T), Adani Defence, Tata Advanced Systems, and the Kalyani Group. The government plans to pick two private players to work alongside Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) and the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), which is leading the design. The selected firms will together receive a share of about ₹15,000 crore in public development funding to help build India’s first stealth fighter.

The AMCA project is not new. DRDO’s Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA) has been working on it for years as the natural successor to the Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) Tejas. But unlike the Tejas, which was almost entirely state-run, the government has decided that the AMCA will be executed as a true public–private partnership. This reflects a strategic shift: New Delhi wants to tap into the private sector’s engineering, manufacturing, and programme management capabilities to reduce delays and cost overruns that have dogged past fighter projects.

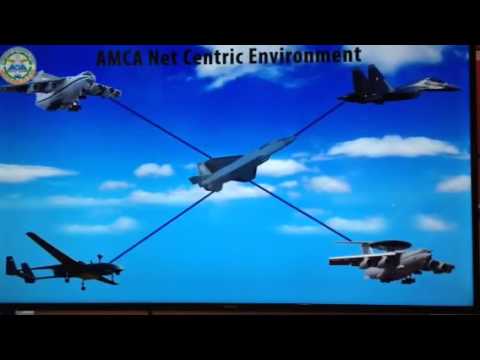

Under the current plan, the AMCA will be a twin-engine, fifth-generation stealth fighter with advanced avionics, internal weapons carriage, and supercruise capability. The first prototype is expected to roll out between 2027 and 2028, with full-scale production and induction targeted around 2033–2034. If the project remains on track.

The Ministry of Defence is assessing multiple proposals not just on price or industrial capacity, but also on long-term commitment to military aerospace manufacturing. The aim is to avoid a repeat of the difficulties faced during the Tejas programme, where HAL was the sole production agency and timelines slipped repeatedly.

For India’s private defence sector, this is a landmark moment. While companies like Tata, L&T, Adani Defence, and Kalyani Group have delivered aerospace components and complete airframes for global manufacturers and the Indian military, none has been invited before to co-own a frontline fighter development programme. The AMCA partnership will give them access to core intellectual property, high-value manufacturing, and sustained orders over decades. The Tata Group leads in airframing experience on the back of its C295 manufacturing partnership with Airbus.

“Whichever two private players make it through this rigorous evaluation will effectively enter the top league of Indian defence aviation,” said a senior industry executive tracking the process. “It’s a rare opportunity because few countries develop stealth fighters and fewer still invite private industry into the core design-to-production process.”

The government has also signalled that it wants the private sector to help attract and retain top talent, bring supply-chain discipline, and explore export potential. India has been keen to project itself as an emerging exporter of advanced defence platforms. A homegrown stealth fighter could be a powerful flagship product if delivered on time and with competitive performance.

India’s air force is in the middle of a critical fleet transition. It has phasing out aging MiG-21s and other legacy Soviet-era jets, while grappling with a shrinking squadron strength even as China rapidly expands its own fifth-generation fleet with the J-20 and incoming FC-21. Pakistan too has begun inducting the Chinese J-10C, a 4.5-generation platform, using them recently too during the Operation Sindoor air battle.

The Indian Air Force has inducted the French Rafale and continues to operate the Su-30MKI and now prepares for the first Tejas Mk1A jets. But its next true generational leap will depend on the AMCA. A stealth fighter designed and built in India would signal self-reliance in a domain dominated by the US, Russia, and China. It would also free India from dependence on foreign suppliers for its most advanced combat aircraft. That ship, however, could sail soon with India now officially known to be contemplating a ‘stopgap’ purchase of a pair of Su-57 squadrons from Russia.

The AMCA programme’s success could determine whether India remains an air power able to compete with regional rivals in the 2030s and beyond. The government’s push to bring in private industry is also meant to avoid the chronic delays that have left India lagging behind in the past. The Tejas, conceived in the 1980s, only entered service decades later. Officials are determined to avoid that trajectory with the AMCA.

Despite the optimism, the challenges are formidable. Stealth design and production are technologically complex and cost-intensive. India will need to master not just the shaping and radar-absorbing materials that make an aircraft stealthy, but also advanced engines, sensors, and electronic warfare systems.

Engine development remains a key bottleneck. India has yet to field a fully indigenous fighter engine of the required class. The current plan is to power early AMCA versions with an imported powerplant while continuing to pursue a joint-venture engine with France’s SAFRAN.

Industrial integration will also test India’s still-maturing private defence ecosystem. While companies like Tata and L&T have experience building components for global aerospace primes, scaling up to lead systems integration on a stealth fighter is a leap. Supply chain maturity, cost control, and quality assurance will be under close scrutiny

If successful, the AMCA’s public–private model could become a template for other strategic programmes, from unmanned combat aircraft to future transport planes. It also represents a conscious attempt by India to build a robust private defence industrial base, in line with the government’s “Atmanirbhar Bharat” vision for self-reliance.

For now, all eyes are on the shortlist that will decide which two Indian firms will help shape the country’s most ambitious military aviation project yet. A final decision is expected once the Ministry of Defence completes its evaluation of capability, past performance, and financial strength. The stakes could hardly be higher, for the Air Force, for India’s defence industry, and for the country’s quest to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the world’s stealth fighter powers.